Accessible Architecture: Intervention in the Cycle of Homeless Youth with Substance Abuse Disorders

Sarah Burgess

0.0 ABSTRACT

Through the analysis and synthesis of homeless facilities, programs, services, and financial reports, along with the experiences of unaccompanied homeless youth, ages 12-24, who struggle with substance abuse, a cycle of homelessness is developed. Temporary, dispersed, and accessible architecture can intervene within the cycle of homelessness to limit the large amounts of youth that are homeless while providing qualitative care. This project identifies the significance of maintaining existing support systems and family infrastructure defined by the homeless communities and recognizes the existing facilities and services available while considering the experiences, basic necessities, and support systems of homeless youth. The development of a campus, consisting of architecture and programs that can meet the needs of homeless youth struggling with substance abuse, such as access to mental and physical health facilities, housing for groups, and education and community integration centers, is defined by interviews with homeless youth and narrative-based research. By providing a multitude of mobile, temporary, and static facilities dispersed throughout the city, homeless youth gain more access to health services, housing, education, business practices, and community preservation and integration. The comparison of the campus to existing practices allows for the ability to determine how successful the project will be based on the amount of qualitative and quantitative care that can be provided within the determined accessible region and within the designated financial amount.

1.0 THE CYCLE OF HOMELESSNESS

1.1 How Does One Become Homeless?

The 2014 documentary “Storied Streets” follows several homeless individuals who share their experiences of how they became homeless and what they face every day while living on the streets. According to Thomas Morgan, the producer and director of the film, it is very easy for someone to become homeless and a majority of people find themselves close to being in a similar situation.

The more people we talk to who know homelessness first hand—families, veterans, young adults—the more I realize that they live lives very similar to mine and yours. When I hear how they have come to find themselves homeless, I know we could all be just a few missteps away from finding ourselves in the same situation. And as they struggle to get out, the rest of society sees them as a nuisance or an eye soar, if they even see them at all.

For many homeless adults, becoming homeless is often the cause of a poor financial situation which inevitably leads to one losing their home. For homeless youth, they often become homeless for different reasons. A majority of unaccompanied youth become homeless for one of three reasons: they aged out or leave the foster system, their biological families kicked them out, or they ran away from home due to being physical and/or sexually assaulted at home. Ultimately, an individual that becomes homeless while in their youth has a higher chance of either staying homeless or becoming homeless when they are an adult. By addressing the specific situations leading to homelessness in youth populations, intervention can be made within the larger cycle of youth to adult homelessness (Storied Streets, 2014).

1.2.Living on the Streets

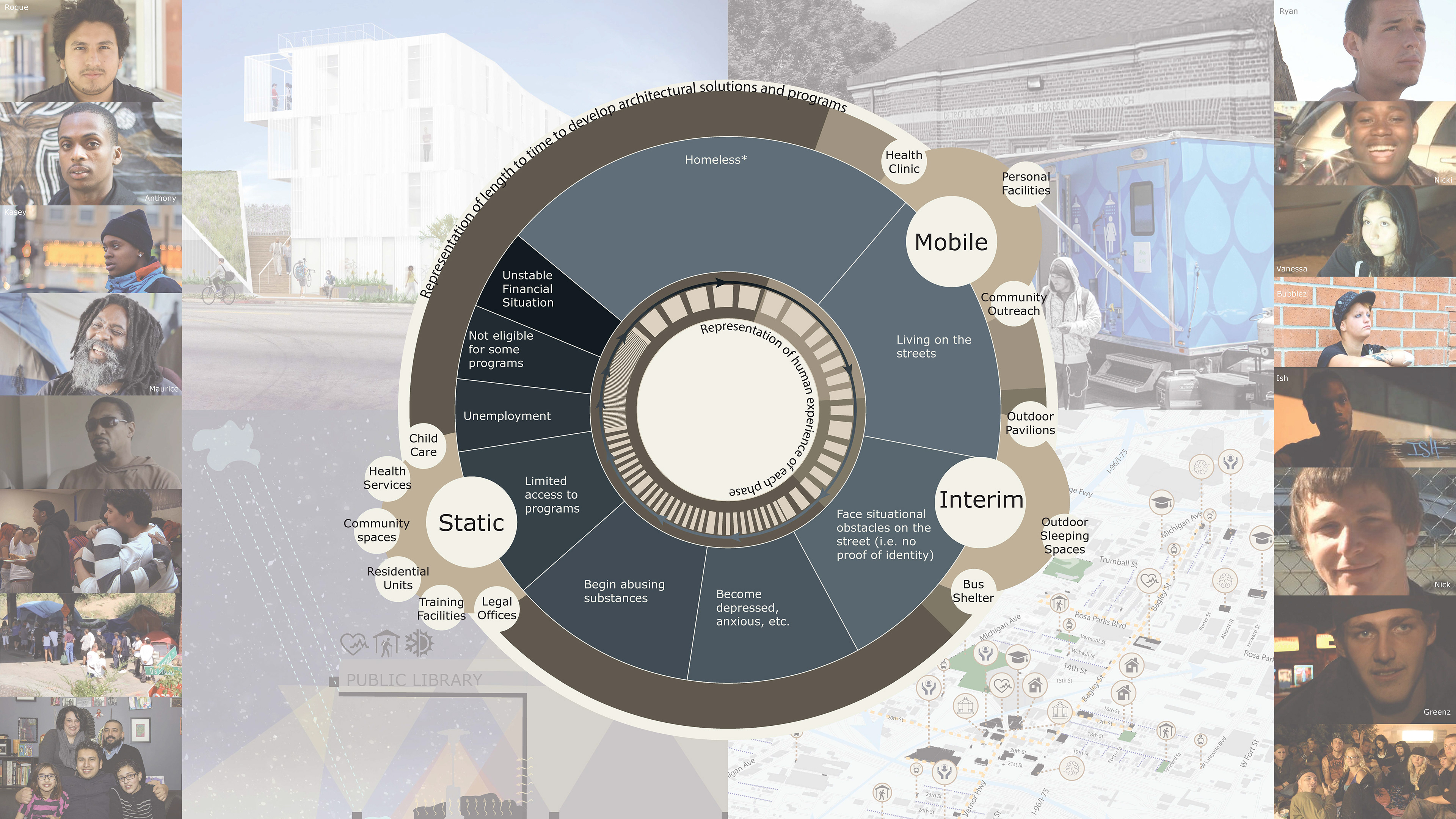

The 2020 documentary “American Street Kid” follows the lives of several homeless youths living on the streets of Los Angeles, California, “Filmmaker Michael Leoni leads us into a world that most people don’t know exists. A world where in order to survive, kids are forced to sell drugs, beg for money, or sell their bodies. They live under bridges, in abandoned houses or anywhere else they can hide to remain safe from the dangers they face daily on the streets” (American Street Kid, 2020). This documentary interviews several homeless youths who are able to discuss how they became homeless, what their lives are like, and their experiences with homeless facilities and services. Los Angeles has one of the largest populations of homeless youth in the United States. But despite the increasing number of the homeless youth population, the documentary highlights the difficulties an individual will have in trying to enter a homeless facility. Most facilities are not open 24/7 and spots are extremely limited. On the streets, homeless youth come to depend on one another to survive rather than rely on facilities and services. Here is where “families” are developed. On the streets, homeless youth develop into groups and communities, these communities are described as families and are a homeless persons’ support system. The “American Street Kid” documentary not only follows homeless youth individuals but follows their relationships with one another and illuminates the developed support systems and “families” one creates while on the streets. The most prominent example of the need for the developed support systems and families is in Bubblez situation. Michael Leoni, the filmmaker of “American Street Kid” became very involved in many of the homeless youth’s lives while creating the documentary. One youth, who called themselves Bubblez, was able to enter one of the facilities through the help and arrangements of Michael Leoni. Later in the documentary, Leoni later found Bubblez back on the streets. In a later interview, Bubblez admitted that they missed their “family”, their friends, and other homeless youth, that had become a part of their support system. Due to limited space, Bubblez support system could not enter the facility. Bubblez was essentially separated from their support system. This example highlighted one of the most significant needs of homeless youth; a support system or “family”. In some way, all of the documentaries highlight the importance of a support system on the street, whether it be a street family, biological family, friends, or support from the community. “Meet me Under the Bridge” is another documentary that highlights the significance of a support system, both in the community and on the streets. If a community does not support the homeless, there is no way for a homeless person to exit the cycle or reintegrate back into society (Refer to Image 01 for a continuation of the cycle) (“Under the Bridge: The Criminalization of Homelessness”, 2015).

1.3. Substance Abuse

Substance abuse rates are substantially high among unaccompanied homeless youth compared to those who are living in family households, unaccompanied youth living on the streets or in shelters have higher rates of reported usage of illicit drugs, alcohol, and marijuana. According to the article “Homelessness in America: Focus on Youth” by the United States Interagency Council on Homelessness

Approximately 11% of all people experiencing homelessness as individuals on a given night are “unaccompanied” youth… [Of] these unaccompanied youth (88% or 36,010 people) were between ages 18 and 25, and 12% (4,789 people) were under age 18. More than half of unaccompanied youth experiencing homelessness were unsheltered (55%), meaning that they were sleeping outdoors, in cars, or in other places not meant for human habitation... Nearly three-fourths (73%) of participants reported using alcohol, almost two-thirds (65%) reported using marijuana, and more than one-third (38%) reported they had used hard drugs (intravenous drugs, inhalants, cocaine, or methamphetamine) in the previous 12 months

In relation to quantitative data shown, several documentaries also explained that while on the streets, the homeless youth have easier access to drugs and alcohol. For a homeless youth living on the streets, being homeless is a dangerous and painful situation. Similar to the other films, the 2018 documentary, “Lost in America”, also follows several homeless youths and illustrates their story as a homeless person, starting with how they became homeless and their experiences living on the streets. “Lost in America” also begins to illustrate the cycle of drug usage in relation to homelessness. One interview stated that

“Being homeless is like being turned into an animal. You’re reduced to surviving. You’re reduced to every single day worrying about food, shelter, water, and safety. You’re in so much pain that you start using, if you weren’t already using.”

For a homeless youth living on the streets, being homeless is a dangerous and painful situation. Combined with having easier access to drugs, the high rates of reported drug use is expected.

1.4. Support Systems, Education, Employment, and Programs

The 2014 documentary, “The Homestretch” dives a bit deeper into the lives of homeless youth and follows three homeless individuals, Roque, Anthony, and Casey. All three individuals had their own experiences of becoming homeless but shared many similarities in their experiences of being homeless. By the end of the documentary, the most significant similarity the three individuals shared was that they each had a support system helping to integrate them into the community and out of the homeless cycle. Roque’s teacher and her family took Roque into their home and provided not only basic necessities but offered support by helping Roque to get the documentation he needed to not only get a job but to also go to college. Anthony had the support of the housing system he was in where he was able to get assistance with employment and job training. Casey also had similar support from the same facility Anthony was a part of, along with support from her biological family. Ultimately, all three members were on their way to exiting the homeless cycle and were able to do so through the help of a support system. The documentary ended with Roque starting college and Anthony working toward a life where he could support his daughter. Unfortunately, like many other homeless youths, Casey struggled with severe substance abuse and was kicked out of the housing program, forcing her to go back to living on the streets, alone and without a support system. According to the article, “Treatment Outcome for Street-Living, Homeless Youth” by Natasha Slesnick, “Older youth are often unable to acquire housing because of other barriers including financial, behavioral/emotional and social prejudice. It is difficult for youth to maintain housing and employment with an active drug addiction and mental health problem, and it is difficult for youth to address substance use and related problems without social stability” (pg.1250). Casey’s situation illuminates how drug abuse in the cycle of homelessness can interfere with eligibility for homeless services and facilities, as well as the continuation of employment or education. For many homeless youths, this is how the cycle continues (refer to image 01). Without the proper forms and identification, along with active drug and mental health issues (refer to image 02 and image 03), it is difficult for them to enter into programs and maintain jobs. This perpetuates the cycle, and for some, heightens their drug use, and they inevitably die within the cycle.

1.5. Perception of the Homeless

Unlike the other documentaries, the 2015 documentary, “Under the Bridge: The Criminalization of Homelessness” focuses on perception by following a homeless community residing under a bridge within the city of Indianapolis, Indiana. Several interviews were conducted during this documentary with homeless members, volunteers, law enforcement, political/city members, and members of existing homeless facilities within Indianapolis. The documentary explains the two different viewpoints people may have towards homeless people and how the perspective of homeless people is essential to addressing the large amounts of the population that struggle with housing instability. For some people in the documentary, they described the homeless as “dirty”, “lazy”, and “want to be homeless” and that the volunteers were making the problem worse by helping to provide for those who do not wish to provide for themselves. On the other end, several members of the homeless community were interviewed as well. In these conversations, many explained how they became homeless and their experience as a homeless person. Of these conversations, there were several things many of the homeless members had in common: The church volunteers were appreciated and described as extremely helpful as they provided basic necessities to those who could not afford to buy them themselves, many were homeless due to financial struggles which eventually led to them losing their homes, and that they would rather live on the streets or go to jail that resides in one of the religious-based homeless facilities within the city. In comparison to other documentaries, the first two elements were extremely common, but this documentary shed more light on the existing facilities than other documentaries. In the city of Indianapolis, almost all of the homeless facilities are religious-based. These facilities require members to attend religious services in order to obtain meals and housing spaces. Many homeless members interviewed in the documentary reported feeling forced and having their rights violated in order to obtain basic necessities such as food and shelter. Whereas in the community they were currently living in, under the bridge, all members helped each other and agreed to abide by basic rules and standards to maintain a healthy space for all homeless members. Essentially, the homeless members had developed their own support system and community that was necessary for individuals to live safely and obtain basic human necessities.

2.0 CURRENT AVAILABLE SERVICES AND FACILITIES

2.1. Comparison of Services

After the analysis of qualitative and quantitative data, evaluation and comparison of existing facilities and programs is essential to understand the architectural relationship and where architectural intervention in the cycle should occur to better address the needs of homeless youth struggling with substance abuse. The top-down approach using scientific data, research papers, and studies specifically looks at homeless people solely as numbers and is an approach almost all architecture uses. The purpose of this approach is to try to help as many homeless people as possible, providing only quantitative care, which means that facilities often provide beds for a few hours a night or hand out food and that is it. Many facilities are not open every day and when they are open, they are only open for a few hours, making it difficult for young homeless people to access the long-term care they need. Facilities also do not often have enough space for individuals, let alone groups and street families. When the facilities do have a space, the waitlist is often six months or more.

2.2. Spaces and Programs

Occupant usage of essential services is increased if on-site facilities are available. The placement of architecture within proximity to public transportation is essential to addressing the number of homeless people. According to Sam Davis in the book Designing for the Homeless: Architecture That Works,

Any facility that serves the homeless is located somewhere, and its immediate neighbors and the surrounding community deserve well-designed buildings that fit into the neighborhood, help residents integrate themselves into the community and alleviate the concerns of local residents that the facility and its clients will compromise their own quality of life (pg.ix)

Having services that are open and within walking distance is extremely important to increase accessibility. Within the Detroit location, revitalizing existing alleyways located between streets helps to include accessibility. This technique can also be used in other cities to increase accessibility to facilities and services.

It is often difficult for unaccompanied homeless youth to access services and facilities due to barriers other than location. They need identification to work and access to showers and bathrooms, charging stations, water, computers, and recovery centers. According to the article, “Treatment Outcome for Street-Living, Homeless Youth”, “Participant barriers include transportation and accessibility to the treatment research site, engagement, development of trust, and tracking for follow-up. Social barriers in treating youth include the provision of housing and psychiatric services for minors who refuse to have parents contacted or social service system involvement.” (pg.1248)

Most places barely have room for one person but they need places that can take whole groups in, whole families that already have internal support created. Homeless youth need housing for the entire group, not just one individual, in order to preserve the already developed communities and “families”. “The shortage of affordable housing is not the only problem facing many of the homeless” (Davis, pg.ix). There are already housing and services available, but lack funding and support and aren’t always open.

3.0 ARCHITECTURAL INTERVENTION

3.1. Necessary Facilities and Programs

Based on all of the research conducted, both quantitative and qualitative data, it has been concluded that the most effective approach of addressing unaccompanied homeless youth with substance abuse through the intervention of architecture can be addressed by implementing the following:

Long-term quality care of large groups. Despite the need to address large quantities of people, it is in the best interest of homeless youth with substance abuse issues to provide quality services that can be accessed over a long period of time. Facilities should be accessible 24/7 and have the ability to take in large groups and “families”. While on the streets, unaccompanied youth become integrated with other unaccompanied youth. These groups develop characteristics similar to families. The kids often refer to others as their family and rely on them for external support and social integration. Ultimately, providing services to the entire family is essential to fostering a healthy environment for all of the unaccompanied youth within the group to receive treatment and access to services to alleviate situational homelessness (“The American Street Kid”).

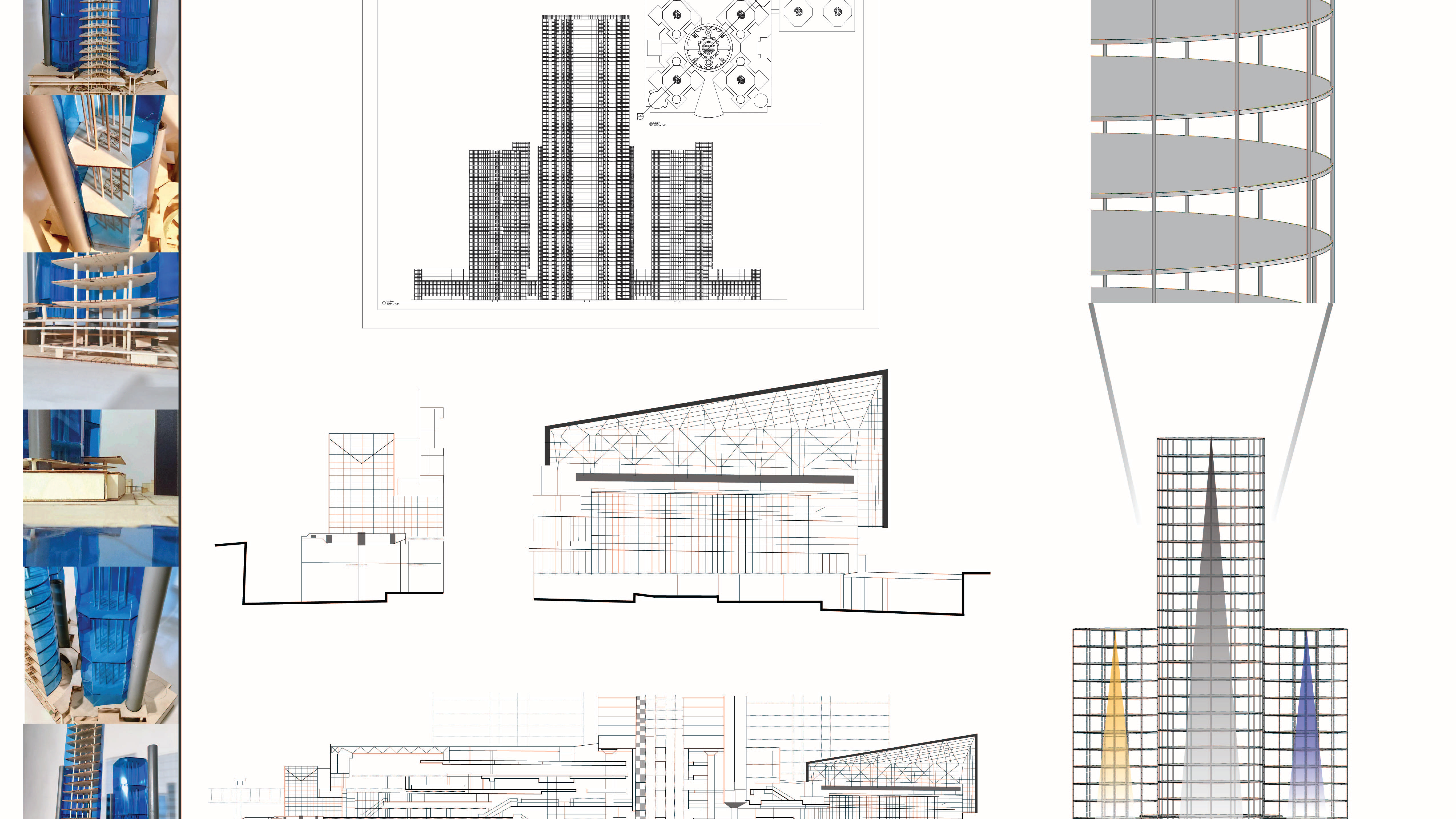

The combination of facilities varying in size is essential to integrate homeless youth into the programs. This idea comes from the fact that almost all architecture is based solely on providing quantitative care (refer to image 04 - case studies). By using facilities varying in size, both quantitative and qualitative care can be provided. Mobile facilities can provide food and quick health services, along with some personal services such as showers, to large amounts of people while spreading information about the other facilities. The use of small, mobile facilities increases accessibility while providing unaccompanied youth with access to information on larger programs where they can receive long-term support and quality care.

Temporary facilities can be used to create shelter and safe spaces for those not eligible for programs or employment, along with those who are not comfortable sleeping at facilities. While static facilities can provide long-term care such as case management, job training, education, and health facilities. Temporary and static facilities can also provide safe overdose spaces for those who are homeless with active drug problems. The use of medium housing units can be successful when spread throughout the city and incorporated with the larger facility. By providing access to transportation to the larger facility, accessibility increases and occupants of the housing units can receive transportation to health services. Through alleviating obstacles, unaccompanied youth have an increasing opportunity to use the facilities. Ultimately the act of dispersing multiple types of facilities throughout the city increases accessibility to a variety of different, necessary programs. It also helps to spread knowledge and increase community engagement, which will help homeless individuals reintegrate back into society and leave the cycle of homelessness.

Temporary facilities can be used to create shelter and safe spaces for those not eligible for programs or employment, along with those who are not comfortable sleeping at facilities. While static facilities can provide long-term care such as case management, job training, education, and health facilities. Temporary and static facilities can also provide safe overdose spaces for those who are homeless with active drug problems. The use of medium housing units can be successful when spread throughout the city and incorporated with the larger facility. By providing access to transportation to the larger facility, accessibility increases and occupants of the housing units can receive transportation to health services. Through alleviating obstacles, unaccompanied youth have an increasing opportunity to use the facilities. Ultimately the act of dispersing multiple types of facilities throughout the city increases accessibility to a variety of different, necessary programs. It also helps to spread knowledge and increase community engagement, which will help homeless individuals reintegrate back into society and leave the cycle of homelessness.

3.2. Building Type and Program

A combination of static and mobile units dispersed throughout the city. The proposal uses double the budget of an existing precedent but is also double the efficiency and coverage, reaching more than double the amount of homeless people.

A combination of static and mobile units dispersed throughout the city. The proposal uses double the budget of an existing precedent but is also double the efficiency and coverage, reaching more than double the amount of homeless people.

The following list of spaces was determined from statements in previous research. All of which came directly from the homeless citizens and people active in the homeless communities.

1. Outdoor sleeping spaces

This is necessary to provide warm, safe, well-lit spaces for those not eligible for programs, or uncomfortable sleeping in facilities. This also allows for large street families to stay together.

2. Residential Units

Lockers

Pet shelter

A majority of existing facilities do not allow pets, despite the fact that nearly 25% of homeless people have pets (National Library of Medicine).

Community Spaces

-Kitchen and living spaces

Based on sevral of the documentaries, it is important for homeless kids to have a place to eat and spend time with their street families

-Technology spaces (access to computers and phones)

-Laundry facilities

-Postal services

Child Care

Health Services

-Overdose center

The leading cause of death among homeless people is from drug overdoses. Having overdose centers, or spaces with free access to Narcan is essential to limiting the amounts of deaths of homeless kids (National Institute on Drug Overdoses). According to “The American Street Kid”, 13 homeless kids die every day. Many of these deaths can be prevented through architectural intervention in the cycle of homelessness

-Counseling offices

-Urgent care/Doctors office

Service Spaces

-Legal Offices

Case management and legal spaces help to eliminate barriers and provide individual attention to the homeless. Despite the many similarities, all homeless kids need individual attention, support, and guidance.

-Training facilities

Security Offices

3. Mobile Services - approx. 300 sqft

1. Outdoor sleeping spaces

This is necessary to provide warm, safe, well-lit spaces for those not eligible for programs, or uncomfortable sleeping in facilities. This also allows for large street families to stay together.

2. Residential Units

Lockers

Pet shelter

A majority of existing facilities do not allow pets, despite the fact that nearly 25% of homeless people have pets (National Library of Medicine).

Community Spaces

-Kitchen and living spaces

Based on sevral of the documentaries, it is important for homeless kids to have a place to eat and spend time with their street families

-Technology spaces (access to computers and phones)

-Laundry facilities

-Postal services

Child Care

Health Services

-Overdose center

The leading cause of death among homeless people is from drug overdoses. Having overdose centers, or spaces with free access to Narcan is essential to limiting the amounts of deaths of homeless kids (National Institute on Drug Overdoses). According to “The American Street Kid”, 13 homeless kids die every day. Many of these deaths can be prevented through architectural intervention in the cycle of homelessness

-Counseling offices

-Urgent care/Doctors office

Service Spaces

-Legal Offices

Case management and legal spaces help to eliminate barriers and provide individual attention to the homeless. Despite the many similarities, all homeless kids need individual attention, support, and guidance.

-Training facilities

Security Offices

3. Mobile Services - approx. 300 sqft

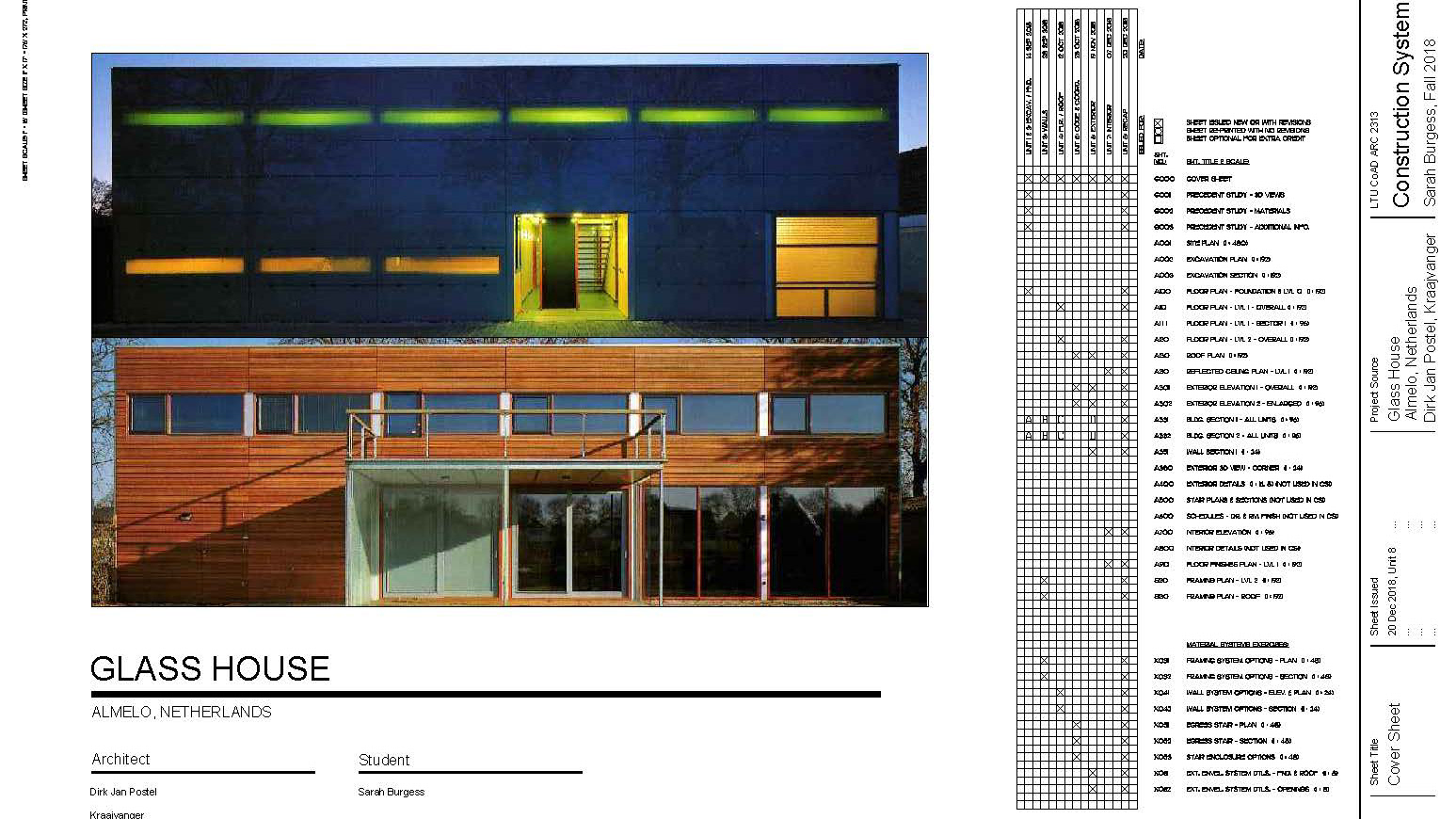

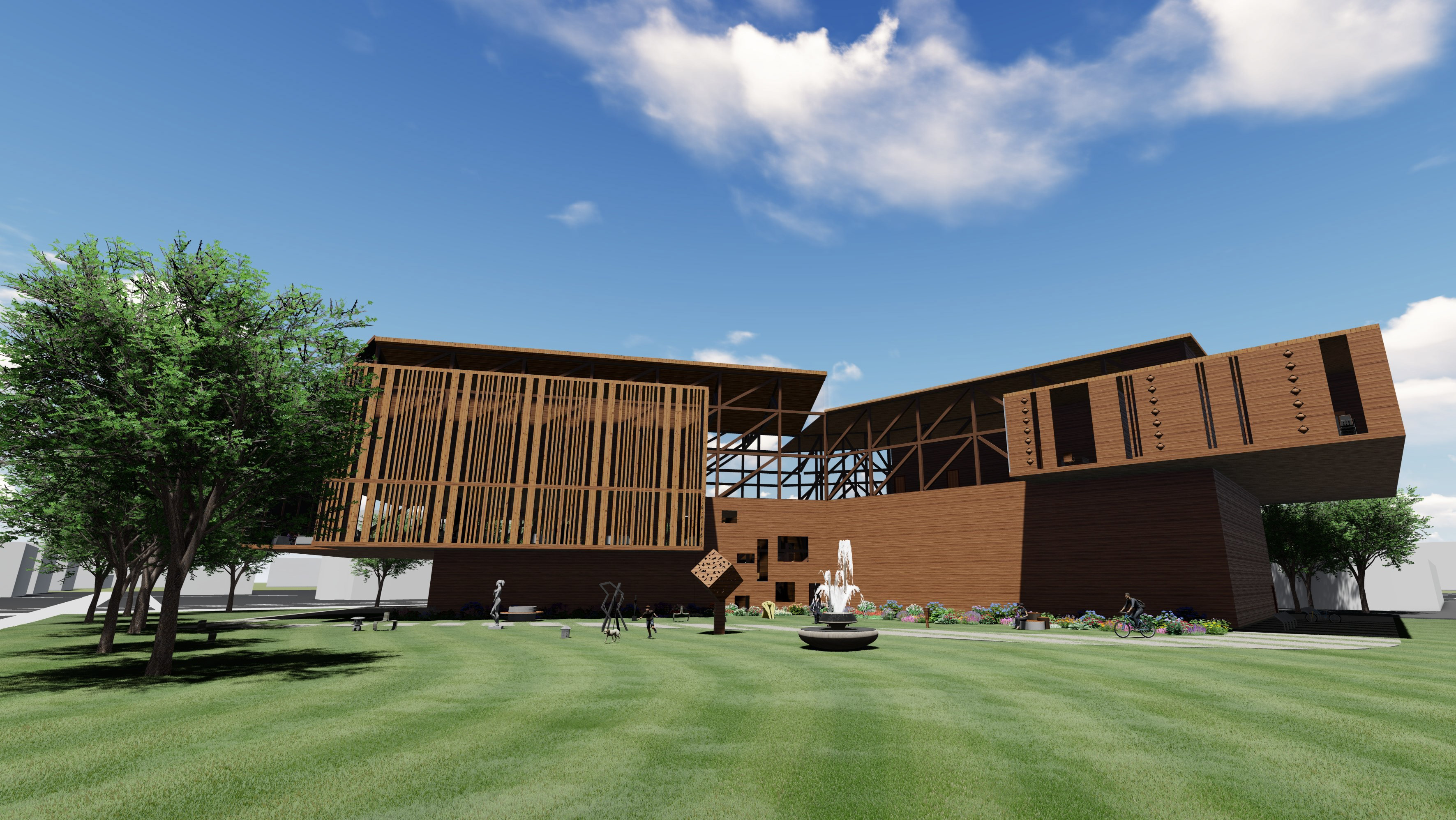

Architectural elements needed to create a successful homeless center (refer to image 04):

• Openings to the street way, integration with the street front

• Use of local materials and construction methods

• Use of local architectural techniques

• Openings and communal spaces

Starting with the mobile facilities, these spaces will house health clinics, personal facilities such as showers, and community outreach, such as access to information. The mobile facilities are essential to reach a larger amount of homeless youth than a static facility can house. These spaces are also essential to address unaccompanied youth that do not have access to basic necessities, information, and may not feel comfortable living in a housing facility. The mobile facilities will also help to inform homeless youth of the other available and accessible services they may need. Second is the interim spaces. These spaces will consist of temporary structures homeless youth and other members of the community can have access to, such as outdoor pavilions, outdoor sleeping spaces, and bus shelters. These pavilions and bus shelters will help to integrate homeless youth with other members of the community and provide safe public spaces for all individuals. Lastly are the static facilities. These hubs will house a majority of the program elements, but will be dispersed throughout the city within a walkable distance to increase accessibility to all program elements.

The combination static, mobile, and temporary architecture will house all program and architectural elements and will allow for intervention in the homeless cycle in multpile areas.